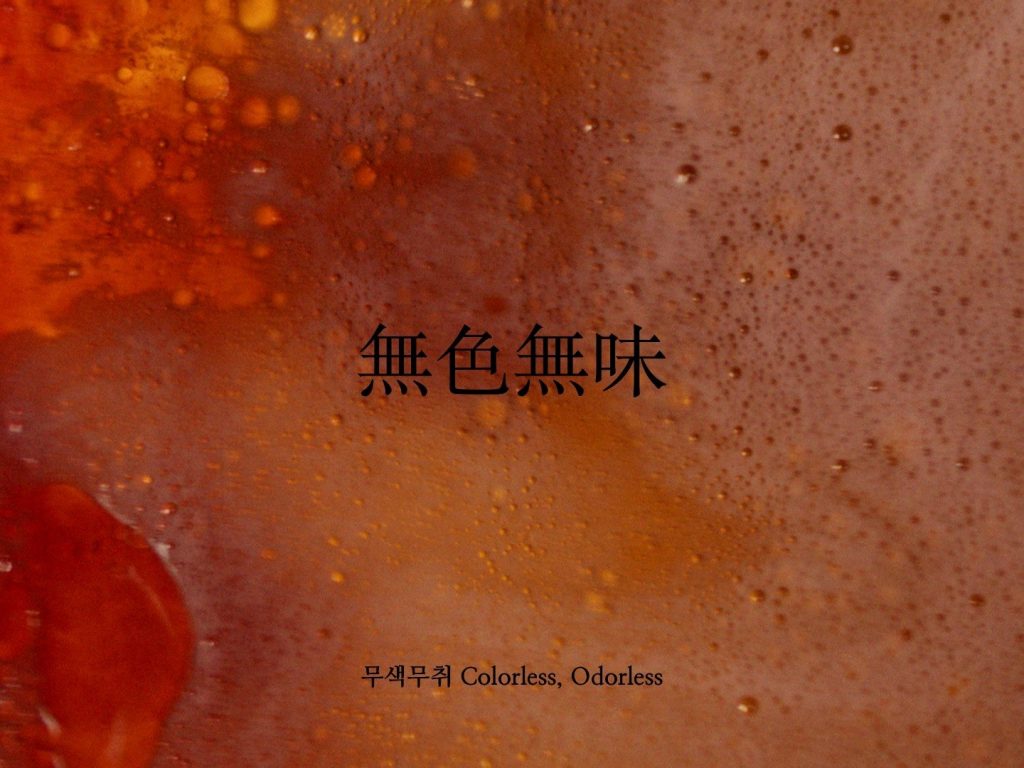

For her debut feature length documentary Colorless, Odorless, which screened as an official selection at the 2025 Jeonju International Film Festival, experimental visual artist and filmmaker Lee Eunhee investigates the toxic and deadly nature of the invisible and odorless components used in semiconductor plants.

In nature the most brightly colored creatures like amphibians and plants are known to be the most poisonous. The ones that animals and humans instinctively understand to pose a threat to our lives. And inversely in the human world of man made creations, what we can’t see or smell tends to be the most dangerous.

First, what is a semiconductor? As defined by Britannica.com:“a semiconductor is “any of a class of crystalline solids intermediate in electrical conductivity between a conductor and an insulator. Semiconductors are employed in the manufacture of various kinds of electronic devices, including diodes, transistors, and integrated circuits.” The technological marvels are derived from specific chemical processes that transform naturally occurring substances silicone crystals such as ingot or sand into pressed almost microscopically thin wafers or discs. It’s in the “clean rooms’ of semiconductor plants that these discs are turned into the microchips that are given their distinctive characteristics that make them usable for a multitude of electronic devices such as cellphones, radios, laptops, TVs, laser printers.

And it’s in these “clean rooms” where strict protocols are adhered to to prevent the contamination of the precious semiconductors, that the very chemical substances used to make these devices such an important part of our technologically driven lives, that the workers, the women who make them are exposed to invisible dangers. Dangers they not only can’t see but in many cases are unable to smell, but have very real, physically debilitating, and even deadly effects.

In 2007, at the age of 27, a young South Korean woman named Hwang Yu-mi died of leukemia, and amongst her personal possessions she left behind a carefully and almost perfectly preserved journal. This journal known as a “clean note” detailed her daily schedule, activities, and performance logs of the factory where she worked, a semiconductor plant owned by the tech giant Samsung.

Yumi wasn’t the only worker at Samsung’s semiconductor plant to become ill as a result of the colorless and odorless killers permeating the air and flowing through the waters of these factories. For decades women and men working in numerous semiconductor plants in South Korea, Taiwan, and all across Asia have been made sick due to the hazardous substances and materials they worked with to make the components required to operate the millions of electronic and digital devices that we have become so dependent on.

Without being provided proper education about the extremely toxic nature of the components and the lack of adequately effective Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs), the health and well being of thousands of women were and continue to be in danger. These women weren’t warned that upon entering the so-called “clean rooms” their lives were being put at risk, that the likelihood of developing cancer, debilitating chronic illnesses that affect their cognitive abilities, hormonal imbalances, and even infertility would rise significantly the moment they stepped through those hermetically sealed doors.

In Colorless, Odorless, Lee Eunhee dives into years of archival footage beginning with promotional news videos extolling the virtuousness of Samsung being a leader in hiring women in a developing industry. She investigates the contradiction of a company and industry being praised for advancing South Korea’s place on the world stage economically and technologically, but the wellbeing of the very women who made the company the success it became were completely and intentionally ignored.

Through multiple discussions with former workers, their family members who campaign for accountability of their deceased loved ones, activists groups such as the researchers and academics studying the environmental and social impact of the chemical waste from the factories, Eunhee creates a very clear picture of how capitalism and social expectations create an environment of pressure where victims are forced to keep silent through a sense of guilt in order for the company and by extension their respective countries to save face.

In candid discussions with her, the women spoke candidly of the pain they suffer from illnesses and multiple surgeries, and feeling conflicted about the social cost of breaking their silence. In Taiwan, she interviewed activists from the Taiwan International Workers Union, who are working tirelessly to bring awareness to just how dangerous these clean rooms are, and the steep price workers are being made to pay for the advancement of technology and people’s obsession with convenience and consumption.

Think of it. Just the consistent trend of companies like Samsung and Apple releasing new cell phone models proactively every year—or bi-annually in Apple’s case the pressure for workers in the semiconductor plants increases to a level to meet unreasonable demands we outside of those rooms can’t comprehend. And that’s what the documentary does. It asks the audience to take some time to think of just what is being required of the women and men working in these factories and the toll they and their families are being expected to suffer through and pay.

In my interview with Eunhee and the film’s producer Kim Shinjae, we spoke about Eunhee’s interest in connecting disability with technology, how her unique approach to filmmaking lead her research for Colorless, Odorless, and how her perception of technology and the way humans interact with it has changed as a result.

Note: This interview was conducted via video, and has been edited for clarity and length.

In looking at your biography and your work Eunhee, you have, I think, you have a very particular interest in studying the human body and technology, and how we as humans have integrated into our society and cultures, and even our bodies, and you study the ways we move our bodies and how those are related. So, I want to ask you, when did your interest between the human body and technology begin and how did you hone in on such a specific field of observation as a filmmaker?

Eunhee: The interest in technology and the phenomenon that is related to technology has already started since I first began making art. For me, technology is actually a very easy way to understand how society functions, because it is ultimately a human creation. It’s not something from out in space. But it is a product of our cultural or economic systems.

When I encounter something problematic or revealing within the tech-industry, or within technological culture more broadly, I feel like it gives insight into how people interact, how we perceive the human body.

I started to make work related to this when I began studying at the art university in 2012, and it just has been a very long continuation of that subject till now.

Also, I must mention my experience of working at a metal manufacturing factory for four years starting in 2018. The factory was dealing with the material used in the production of technological devices and machines. There, I realized how all these digital products come from very physical materials. All these virtual things from the digital world…these intangible things are made of, you know, the materials extracted from the Earth.

Then I started to trace the full life cycle of technological objects, how they are made, consumed, or how they’re disposed of. It ended up with me making Colorless, Odorless, which is about the human cost of producing state-of-the-art technology.

Yes. I watched some of the short films that you have on the website, and a few of them stuck out to me, like, for instance, The Flat Blue Sky (2016), AHANDINACAP (2020), and Mechanics of Stress (2023), which deals with the stress test that engineers use to test things like steel beams, and concrete, to see how much pressure they can sustain before they break and fall apart and shatter becoming useless or a danger us. And in AHANDINACAP, you dealt with how disabled people use technology to help with their disability, but the way you look at it is very interesting, as you talk about people wanting to fix disability, not necessarily for the benefit of the disabled, but for the benefit of society.

Society advocates for fixing disabled people so they can work and therefore be seen as productive and useful to society, as though people are only useful as disabled people if we can be profitable and beneficial, and I kind of saw this throughline in all of your films.

So, I want to ask you just about that, about looking at disability, because it does tie into Colorless, Odorless, because it’s talking technology, working with technology itself disables the workers. It disables these women. But before you get to how technology disables us, a lot of your films are about how we use technology to “stop being disabled.” So just talk to me about that particular aspect of your previous work.

Eunhee: I think by the time I got to learn about disability studies, it completely changed the perspective of how I looked at society. What disability studies suggest is that impairments are not defined by physical deficiencies, but rather by how society labels and interprets them. In this way, disability studies challenge and subvert the traditional understanding of disability and its relationship with society. It also made me reconsider the idea of “defect”. Perhaps what defines something as a defect might be the result of social norms and perspectives, rather than the condition itself.

It was a perspective shift for me, and I wanted to carry it over into how I think about technology. You know, technology can also be broken or dysfunctional, and at some point it should be repaired, or it should be disposed of. Who’s gonna repair that? Today, we often imagine technology as something that will fix us, something that is evolving beyond us. But technology also relies on human labor to function. When it breaks down, it is human – often invisible workers – who fix and maintain it.

This also made me reconsider what “work” means. The act of working is not just an economic pursuit. The people that I met during the film production, who had worked over 20 years in semiconductor factories, they didn’t just work for money or survival. They took pride in their work, devoting their youth to it.

Their stories and the environments they worked it, reveal so much about human experience. That is where the connection lies for me, in asking what labor is, what its value is, how it is entangled with technology and machines. This interaction is not just linear or one directional, they are interconnected.

Shinjae: To add some additional context, she was always interested in the underlying aspects of cutting-edge technology. But at the same time, actually, she started from books she read related to her personal experience.

Eunhee: It doesn’t come from something I directly experienced. I’ve been more of a caregiver. One of my family members has been very sick, and we have gone through many treatments and rounds of rehabilitation. As a caregiver, I got to encounter a range of new medical technologies and treatments in hospital.

Some of them feel almost like simulations. Like VR-based therapy or large mechanical frames that suspend patients like marionettes to make them walk. It gave me the feeling of doubts: Does that really help? It seems that technology must advance and constantly invent something new. But I feel like this non-stop innovation and creation are driven more by the economic demand than human necessity.

Shinjae: So for me, it was interesting because Eunhee was connecting her interest to labor in a way that was more obvious than her previous works. She was connecting sick bodies and defects of the machinery and defects in the industry and also our society as well. So, I think working with her, I could also follow the underlying connected layers in everything you know. All the digital devices and so on.

Carolyn: Is that what made you interested in working with Eunhee? Because, in looking at the write-ups of some of the film projects, I noticed that your first write-up is around 2022, and that was for Machines Don’t Die. So was that when the two of you began collaborating together?

Eunhee: We already had a good understanding of each other’s interest since I participated in a group exhibition curated by Shinjae, before we actually started making Machines Don’t Die (2022) together as the artist and the producer. The collaboration was suggested by Shinjae, commissioned by the Seoul Museum of Art.

Even though the settings and factories in the film are in South Korea and it’s dealing with situations that specifically affect South Korean people, it can be applied globally because we all use technology. We use Samsung products. My phone is a Samsung.

Shinjae: Yes, you’re right.

Eunhee: And there’s iPhones.

For you, Shinjae, as a curator, when you began working with Eunhee, you mentioned that you saw certain throughlines in the stories, and because of the type of work that Eunhee does is very experimental and she’s dealing with very specific ideas of humanity and technology and our place in culture and society in relation to technology, as a producer, how do you support and facilitate an artist like Eunhee when there might be people who don’t quite understand what she’s going for thematically and artistically?

I imagine that in order to facilitate her you have to have a deep understanding of her art and what she’s thinking to in a sense interpret her work for others.

Shinjae: You mentioned the word facilitator, and actually, I think that my role is not like a typical film producer, but more of a mediator or translator.

If I can mention a bit about my background, my undergraduate was actually in art studies, but I studied creative writing for the MFA. So, I don’t feel like a museum person. I’m more interested in production, and, you know, producing something, rather than reading or distancing myself from the work. So I started my career as an intern from KOFIC, and there, my role was collecting screeners back then, and DVDs and CDs for the programmers at Cannes and Venice and… people who were going to take a look at all the Korean films there at the viewing room. KOFIC provides support to the filmmakers and festivals in that aspect.

Back then as an intern, I was visiting Venice Film Festival for the Korean Film Night, and I remember that I thought “Oh, I have to be here with something, rather than just supporting or organizing a party.” there. I think that was kind of the seed for me. Afterwards, I started working at the DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, but my interest was very specific, because my interest started with non fiction films produced by filmmakers who have visual art backgrounds. Afterwards, I felt maybe artist films and lens-based works by visual artists can be something I worked on in the future, and maybe I could be the mediator for that. So afterwards, I worked at an international sales and distribution company for boutique Asian arts documentaries.

But it was very short, seven or eight months, and then…I don’t know, just my life brought me to the arts scene and I served as a contracted curatorial assistant for Sharjah Art Foundation and the Asian Art Center Theatre, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Arts, Korea in the film and video department, and Seoul Mediacity Biennale later. There, I worked with several art producers who worked with visual artists outside of Korea, but here in Korea, especially in the visual arts scene, normally you get a maximum of $8,000 for the visual artist to make a moving image.

Carolyn: That’s not a lot of money.

Shinjae: No, that’s not a lot at all. So, you know, it’s not possible for the artist, for the project, the film producers can be involved, you know, they cannot even pay for that sometimes. But I thought, oh, we need film producers here. That’s why I started my research about moving image production and I visited European countries first, because there was a kind of moving image production and distribution initiative called On & For Production and Distribution, organized by four artists and a producer collective in Brussels.

I also visited Paris and met an independent curator and film producer from Guadeloupe now based in France who organized screenings in his space called Espace Khiasma, and who also works with artists and filmmakers such as Eric Baudelaire and Mati Diop. Then I went to Bangkok to look into their artist film scene. I was following my own interests to understand how the ecosystem worked because I couldn’t have a role model here in Korea, because I didn’t want to be a typical producer in the film industry who makes documentary feature films or a performance producer.

I also drew references from dance performances and non-traditional performance productions. It took me several years to fully recognize and embrace artist film production as part of my curatorial practice.

Eunhee, something that I talk about a lot on social media is how as humans, we create technology, we create things, and we turn around and worship them, and in a sense I see that related to what you said earlier about humans thinking that technology will fix us, and that’s happening since the advent of the internet, the worldwide web.

But I would say, more recently, within the last 20 years, with regards to our cell phones and TV, and now AI are almost seen as our gods. We’re never without our cell phones. We walk around with them in our hands even when not using them like they’re permanently attached to us. But, more recently, there’s something that I’m very worried about, and it’s AI.

There’s a movement within the AI tech space by people whom I call neotech-colonialists, who are trying to position AI, generativeAI as a type of newGod to humans. They’re saying things like ‘we’ve created this technology and it’s amazing. So amazing that it’s better than us human beings. ‘So now, I’d like to ask you to talk about that concept of worshiping technology, even though we’re the ones who built it and also need to fix it, because how can something that we consider a God need repairing by the same people who created it?

Talk a bit about that, because that does tie in a lot to Colorless, Orderless, and to these companies and the technology that these women and men in the semiconductor plants in South Korea and all across Asia are working with and manufacturing with their own hands and at the cost of their health are being looked at as being above them, above us by technocrats, men particularly wealthy white men in North America like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, which in itself is an irony.

Eunhee: That’s a difficult question.

Carolyn: I know.

Eunhee: People often ask me after seeing my work, “So, do you want to say that technology is bad? in a dystopian way, it is going to harm us?” and I cannot really say I agree with that. I don’t want to define technology into one single justification. Technology is not one simple thing, it’s a complex entanglement of many elements of human society.

I don’t think we worship technology itself. What we’ve worshiped is probably money. Tech industries are fueled by the stock market speculation. Companies like Samsung and TSMC are not just corporations, they are deeply tied to global capital. Their growth is a shared desire, not just of CEOs, but of shareholders, governments and the public who associate these companies with national development.

This kind of collective pressure builds up all these problems sometimes. When problems arise, instead of addressing them, companies often try to cover them up, with the fear of damaging their market value and reputation.

One example is the health risks affecting the female factory workers that were hidden for a long time. The semiconductor industry in South Korea is supported by the whole nation, as the chance of economical leap. A lot of the media back then framed women workers as symbols of national development, praising their “nimble fingers” and their natural suitability for delicate tasks. But the health issue has never been focused on. People wanted to believe that these advancements were purely good, that they would make us rich and improve our lives.

So, worship of technology is not the main point. It’s more about how our collective desires are projected onto it. Our desire for wealth, control, speed, and flawlessness. For example, I think surveillance technology reflects a human desire to know everything, to see without deeper investigation, to simplify complex realities into simple data.

Carolyn: Yeah. It’s about simplification and instant gratification using technology.

Shinjae: I think you already know, but historically, big companies like Samsung have been supported by the government and politicians and they work closely with Samsung. There was even a situation when the vice president of Samsung was jailed for offering bribes in response to the president’s request for support.

So, actually, I’m living close to the Samsung semiconductor factory complex in which one of the interviewees in the film worked. Along the roads, I saw banners celebrating the selection of our region as the site for the semiconductor industry cluster under the previous administration.

Carolyn: The interview subject in the film you referred to is the lady who worked on the processing line and got sick with ear infections and had to have a hysterectomy, correct?

Shinjae: That’s right.

So we’re really getting into the meat of the film now. You’ve both mentioned how Samsung the company itself is seen as the pride of South Korea because it’s known the world over by everyone and we’ve spoken of how Samsung devices are used the world over, so now I want to talk about the women themselves.

The film begins with the story of Hwang Yumi, who died at 22 years old of acute leukaemia in 2007. She worked for Samsung on the semiconductor processing production line. Eunhee, I read online that there had been another company from which Samsung had bought out the rights to operate their semiconductor plants and basically took control of the whole industry in South Korea around 1974. And as you mentioned Eunhee, in their marketing they spoke of women being suited to those jobs of building the delicate parts because of their strength and nimble fingers and as seen in some of the archival footage used in the film.

I found it particularly interesting the company used women working in the plant as a way to position it as being feminist. As the company was being supportive of women and women’s rights, and their right to work in tech spaces. This was different because at this point in time tech and sciences were very male dominated fields. And initially this seemed like a good thing, but as Samsung was using the message of equality, women were (and still are) the predominant victims of the company’s negligence. They were becoming sick due to the lack of care for their health. They didn’t have proper PPEs, or proper training on how to work with the components and all of the toxic chemicals used in the process of making them.

There wasn’t proper ventilation or sanitary conditions. In watching the film these images really stood out to me through the discussions with all of the South Korean and Taiwanese workers and activists whom you spoke to. The conditions of those labs and the perceptions people have of them are what prompted the title of the film.

Inside these factories are the famed “clean rooms”, places where all the considerations of cleanliness are for the products being made, but not for the humans making them. To track their production tasks, workers keep what are known as a “clean note”, and Hwang Yu-mi has one and because of the treatment it received to keep it free of contaminants, her book has outlasted her. And that really shook me. It struck me that the reason we have a record of how she felt sick is because the company has stricter protocols of how she had to care for it than the company had for her life.

Eunhee: The image of the “clean note” and the issues of health risks faced by semiconductor factory workers were already exposed in several documentaries and media around 2014, which was 10 years ago.

So, many Koreans were aware of these incidents then. But they don’t know that even 10 years later, the same things are still happening. Not only in Samsung but across many other companies, including outsourcing firms and factories in other countries. The same pattern keeps repeating where the female workers are being silenced, especially because a lot of the diseases and sicknesses that they get were so private.

For example, the risks to their reproductive health. A lot of women working in the semiconductor factories experience of miscarriage. Because those issues are seen as “women’s problems”, they were discouraged from speaking out. These silencing strategies are very effective for the company, especially because the causes of illness are invisible—there’s no obvious substance to blame, no clear proof to point to.

The women workers were not able to share their experience to the public, not just because of shame, but also because of the pride they once had in being employed by a prestigious company.

The people I met; they often said “Can I even talk about this? I was proud to work there. I don’t want people to think I’m just complaining.” and I think it happens very strategically in this semiconductor or electronic industry, not only in Korea, and that’s why I thought we must talk about this issue in the film.

Although that earlier documentary raised public awareness, these issues were never truly resolved in 2014. Many people think “Oh, we thought it was actually finished. We thought the government was dealing with it. We thought the environment in the factories got better.” But it is not. A lot of the testimony of the female South Korean workers and the migrant workers are still saying exactly the same thing as was said 10 years ago.

In this film, we didn’t just focus on Samsung, but also on its outsourcing companies. Tighter regulations have led major corporations to offload dangerous or toxic work to subcontractors, both locally and overseas. This isn’t unique to Samsung—it’s also happening in places like Taiwan, where the economic strategy similarly relies on electronic manufacturing.

Workers in Taiwan who produce iPhones or ASUS laptops shared similar stories. Female workers are suffering from breast cancer and other cancers, but with almost no media coverage. So, yeah, I think I wanted to update the story that have not been resolved yet.

The other thing that really stood out to me with the film’s title Colorless, Odorless not only because it relates the invisibility of the vaporised chemicals in the atmosphere of the clean rooms, some of them also don’t have odors. And with the colorless, and odorlessness, the film really made me think about how they also come with silence. So like, those three things can kind of go hand in hand, colorless, odorless, and silence, with regards to the women not being able to speak out. They’ve been essentially silenced by the job itself, even if the company doesn’t have to necessarily exert pressure on them directly.

They’re also silenced by the expectations society placed on them for having these jobs by saying “You’re a woman working this field, so you should be grateful. You can provide for your family, you can buy food, you can buy clothing.”, so as you were saying it creates this idea that these women I don’t have the right to speak up because they are grateful for what this job has provided for them. Even as it’s killing them.

Close to the end of the film, the same former Samsung employee you spoke of earlier does say that that’s what makes her feel very conflicted which she revealed when she said ” I don’t work there anymore, but I’m still living with the effects of this.”

There always comes a time when we have to ask if the silence is worth it? Is the silence worth the consequences, you know? And, and I think that’s something really important the film made me think about and it’s not just about what happens inside the factories. It’s about what happens outside of them, because what happens there doesn’t stay there. It spreads out, and not just with regards to the toxic chemicals leaching into the water and into the environment, but it affects their lives, their families and I think the society as well because even though people might not think about it like but as is highlighted in the film thousands of people have died from this, and that has an effect on society, that affects the population.

So I was wondering if I was thinking too much about this, but as I pay attention to South Korean politics and culture there’s a situation that’s become quite a significant worry for the country right now is the drastic drop in the human birth rate. And I was thinking, if you have from just one company, Samsung in this case, a situation that for thousands of women has caused their deaths, chronic illnesses that lead to the inability to have children, and for those who do have children they’re born with physical and cognitive disabilities, which means they also can’t go on to have children.

I just kept thinking this one ‘situation’ alone could have a dramatic effect on the birth rate, because these are people that can’t, in a way, contribute to the population numbers. So I was wondering, am I thinking about this too much, but I…don’t think I am.

Shinjae: It’s the same for me, I’ve been interested in the aftermath of the East Japan earthquake (2011) from the perspective of [it being a] slow disaster because of the radioactive contamination there, and the contaminated water coming from Japan. But in the process of my research on this, I’ve realized that this is also a slow disaster happening in our bodies.

I want us to talk a bit now about the activists whom you spoke to in Taiwan, because in my research, I saw that while South Korea is one of the largest manufacturers of the chips for semiconductors, TTaiwan actually has the most semiconductor plants, and next to South Korea, Taiwan is the largest producers and manufacturers of electronics like laptops, PCs, printers, and cell phone components.

Tell me about going to Taiwan and speaking to the members of various activist organizations like the Taiwan International Workers Union. You spoke to them about their work in the lamination labs, clean rooms, and the occupational injuries suffered in places like Tao Yan.

Is there anything you were surprised to learn about specific instances that happened in Taiwan, that you perhaps may not have observed with South Korea?

Eunhee: I found more similarities than differences between the cases in Taiwan and Korea. The history of the RCA factory’s arrival in Taiwan, how this American factory came to Taiwan and the entire nation rallied around electronics production as a pathway to economic growth. Also, the mass number of women employed to RCA is very similar to cases in South Korea.

It was the same pattern the women workers were not informed about the dangers of the chemicals they were handling. They were not given proper masks or bodysuits to protect themselves. There was also the social pressure of working in a good company, being silenced.

But the thing is, this problem surfaced a bit earlier in Taiwan. As a result, NGOs, independent media, and civil rights groups there have a longer and somewhat stronger history of activism around these issues. But they also have a much higher number of deaths from cancers and other illnesses linked to toxic exposures in the factories.

When I reached out to visit, they welcomed me right away. They had a goal. Not just compensation—they’re now trying to build a memorial park where the RCA factory used to stand. Since the factory has been shut down, they want that place to remind people of the risks involved in this kind of work. I was honestly very moved by how clear and motivated they were about their vision for the future.

We also tried to go to Vietnam, but the NGO that we contacted said they were under surveillance by the government, so the visit was postponed. The Vietnamese government seems to be ignoring the issue—because companies like Samsung making factories in their country are so important for the economy.

It’s just like when the American company RCA came to Taiwan, it was great for their economy, so they close their eyes to other dangerous risks, and now in Vietnam women are getting sick.

To close out the interview, something that you said in the film that I found very poignant is that the only evidence they women have are the testimonies of their bodies because there’s no written evidence. All they have are their memories of the smells and experiences, and it made me think of the Radium Girls who died of radiation poisoning from working in watch factories.

The evidence they had of what happened to them was their bodies becoming sick after working in those factories, and how they glowed in their graves.

So, I’d like you to talk about the body being the testimony of an invisible force harming these women.

Eunhee: But the sad thing is, even though there’s medical evidence—like documents, test results, MRIs—that show harm to the body, it often doesn’t help in court. The factories always deny responsibility, even when the data is there.

So in my work, I don’t try to scientifically prove that “this specific illness was caused by this specific chemical”, because that’s not my role. I don’t want people seeing this work to have doubts like “Are they really sure that they got sick in the semiconductor factory? Maybe they want something else.”

What I try to do is make the audience feel connected, to these women workers, to the interviewees. For example, one of the women I interviewed had undergone ear surgery, and she shared her MRI scans with me. And I put a lot of effort into using certain sound and visual effects so that people can receive or feel some emotion towards them.

I used their words, their stories, and their actual bodily images, so that the audience can imagine themselves in those situations. To think, “Maybe this isn’t just some distant woman’s story. Maybe it’s connected to me too.” Or people would also begin to reflect on the devices they use every day—the phones in their hands, the laptops they type on—and realize that these things were made by people like her.

Carolyn Hinds

Freelance Film Critic, Journalist, Podcaster & YouTuber

African American Film Critics Association Member, Tomatometer-Approved Critic

Host & Producer Carolyn Talks…, and So Here’s What Happened! Podcast

Bylines at Authory.com/CarolynHinds

Twitter & Instagram: @CarrieCnh12

#JeonjuIFF2025 #ColorlessOrderless #DirectorLeeEunhee #ProducerKimShinja #kcrush #kcrushfilminterview #film #semiconductor #manmade #kcrushamerica #kcrushmagazine #kcrushnews #radiationpoising #Taiwan #TheFlatBlueSky2016 #technology #disabled #AHANDINACAP

Leave a Reply